ALIEN: EARTH | A POST-MORTEM REFLECTION

Wendy, Joe & Nibbs

It’s been nearly three weeks since the season finale of Alien: Earth released on FX, and as expected, fandom has been all over the place. At Perfect Organism: The Alien Saga Podcast, we were deep in the trenches covering the series from Noah Hawley, starting back in February. What followed was a whirlwind of interviews, aftershows, convention appearances, and sleepless nights. Now that the dust has settled, so have my thoughts.

Alien has always been a tough nut to crack. Since 1986, we’ve been chasing that elusive feeling, the mystery, the terror, the humanity that defined the first two films. When Episode 8 of Alien: Earth dropped, it became clear that, once again, we were facing a divided fandom and a product with both much to love and much to question.

In recent years, each new Alien entry, from Prometheus to Romulus to Earth, has arrived under a flood of director commentary and pre-release promises. Fede Álvarez warned of the dangers of “member berries,” while Noah Hawley vowed to re-mystify Giger’s perfect organism. Yet, when their projects finally reached us, what was said and what was delivered didn’t quite align. That dissonance erodes audience trust. Film and television landscape has dramatically changed. Gone are the days of intimate production diaries and year-long anticipation cycles. Marketing now typically begins three months before release, and the creative conversation often stops once the show premieres. Alien: Earth spent over five years in production limbo, from COVID shutdowns to the writers’ strike, obstacle after obstacle stood in the way. For a while, it seemed it might never happen. Then, suddenly, the strikes ended and filming restarted.

Kirsch is taken down during a fight with Morrow.

From the start, fans were cautious. The very title Alien: Earth carried weight, a callback to Alien 3’s original teaser, which famously promised “on Earth, everyone can hear you scream” before Fox pivoted, brought back Ripley, and delivered something far stranger. For many fans, that history remains a ghost haunting every new announcement. Like Ripley herself, the Alien fandom suffers from a kind of collective PTSD. We get excited, we hope, and too often we’re left disappointed. The question isn’t just whether studios can “get it right” anymore, it’s whether anyone truly understands what “right” even means for this franchise. Over the last several years, covering this series has become more than a creative pursuit. It’s become a study in human behavior. With every new installment, the same pattern repeats itself: anticipation gives way to anxiety, and anxiety gives way to outrage. The conversations we once had about art, ideas, and craft have turned into tribal declarations about who is “for” or “against” something.

When we as a podcast praised Alien: Earth, we were accused of being paid by FX. When we criticized it, we were accused of hating Alien or failing to “get it.” If we tried to hold space for both perspectives, we were told we were censoring the voices of those who disagreed. Division once again has reached a fever pitch where a difference in opinion feels like a crime. Lines are drawn in the sand. Longtime friends in the fandom stop speaking. Others are made to feel small or stupid for seeing something differently. Some of the comments hurled online carry such venom you’d think a sacred trust had been broken, not that a TV show had failed to meet expectations. The result is a fandom fraying from within. The more it happens, the more the community erodes. The line between critique and cruelty blurs until no one remembers what side they’re on. I’ve seen creators step away entirely, burned out by the very audience they once sought to entertain. I’ve seen thoughtful people withdraw from conversation because it no longer feels safe to love something publicly.

An injured Hicks waits on the drop ship for Ripley to return.

The irony, of course, is that Alien has always been about survival through unity, people of different backgrounds coming together to endure the impossible. But online, the opposite has happened. What should be shared love has turned into a competition for moral superiority. The fandom, in many ways, mirrors the chaos of the worlds it adores. It’s exhausting. And yet, we stay, because something about this universe still means something to us. The Alien IP might be the most difficult sandbox to write for. The first two films, Ridley Scott’s Alien and James Cameron’s Aliens, are triumphs of vision and script. They’re about tension, psychology, and detail. The writing makes or breaks it. And lately, the writing has felt unfinished, even when the world-building and performances shine.

Hawley’s scripts reportedly sat ready for years before cameras rolled, which makes it all the more curious that so many story threads felt undercooked or unexamined. Alien has always been in-part about precision, the small choices, the logic of the world. There’s a reason fans still debate Ripley’s adherence to protocol, or Ash’s violation of it. We care about cause and effect. Why didn’t a Weyland-Yutani representative chase the crew of the Corbellan as it ascended to the Renaissance space station in Alien: Romulus? Why does Alien: Earth’s Wendy succeed while the other hybrids fail? If Boy Kavalier can literally see through the eyes of his hybrids, how does he miss what’s right in front of him? The more you look, the more the fabric frays. That said, Alien: Earth isn’t without soul. Whether you loved it, hated it, or landed somewhere in the middle, the series offered something fresh: new characters with agency, a story uninterested in nostalgia-baiting. That alone deserves respect.

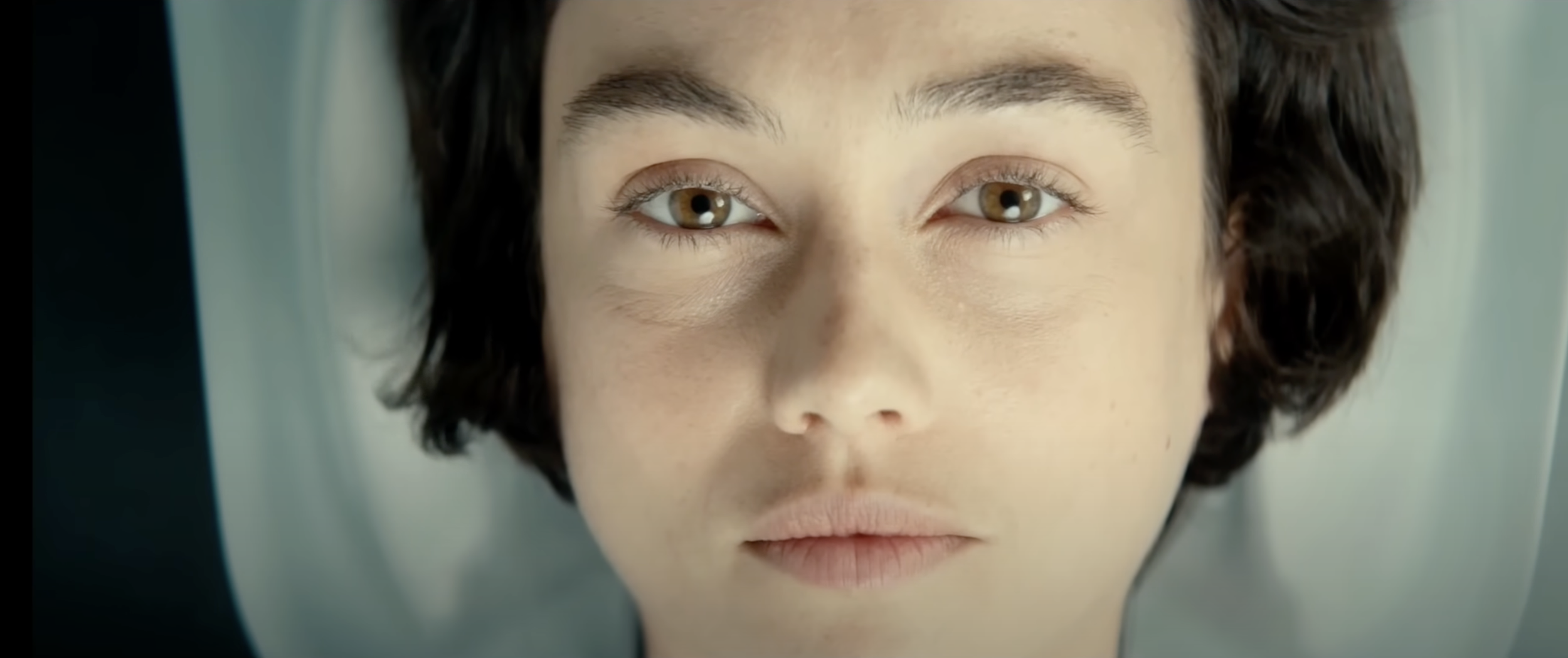

Sydney Chandler as Wendy.

Where Earth truly shines is in the questions it asks. What does it mean to be human? What is humanity, exactly? Is it something worth preserving? These are big, bold questions, closer in spirit to Blade Runner than to Alien. For some, that divergence was too great. For others, it was exactly the evolution the series needed. But by the finale, audience enthusiasm had cooled. Ratings dropped, conversations turned skeptical, and the season ended not with a bang, but a quiet thud. As of this writing, FX has yet to announce a renewal. For me, the show began to lose its footing in how it depicted the creature itself. That unraveling began in Episode 5, when the alien’s movements started to feel strange, stylized, almost dance-like. By Episode 7, Wendy, played brilliantly by Sydney Chandler, was petting the xenomorph in an open field, surrounded by onlookers who treated it less like a cosmic nightmare and more like a curious animal.

By the end, the creature had become something to command, even summon on cue. For all of Hawley’s strengths, his character work, his ideas, this particular choice undercut the series’ central terror. The alien isn’t a pet, or a symbol to be tamed. It’s unknowable, and that’s what makes it terrifying.

A Xenomorph attacks Joe Hermit.

The creature’s design, too, left many fans uneasy. Hawley explained that he’d leaned toward an “earth-like insect” aesthetic, hoping to make it feel grounded. But in doing so, he stripped it of its otherworldly essence. Giger’s design was never meant to be familiar. It was meant to be unreadable. By the final moments of Alien: Earth, the Xenomorph looked less like a nightmare from beyond and more like a man in a rubber suit, the worst fate imaginable for this creature. It had been robbed of all mystery, all agency, all power. If Alien: Earth returns, I hope what’s renewed isn’t just the story, but the reverence, for the creature, the myth, and the atmosphere that made this universe timeless. The Alien saga doesn’t need bigger worlds; it needs deeper ones. Fear, silence, and mystery built this franchise, and they can save it again. I also hope the fandom finds that same balance, to debate without hostility, to disagree without tearing down, and to remember that love for this universe is the one thing we all share.

Jaime Prater for Perfect Organism: The Alien Saga Podcast